The Saturday before last, November 14, I was at the Salton Sea with Terry Nakazono.

Terry was rolling with a new scope – a Meade Polaris 114. It’s an f/8.8 reflector – the 1000mm focal length makes it a bit longer than the 900mm, f/7.9 Orion XT4.5 (which London has). UPDATE Nov. 29: Terry writes, “It’s a standard 900mm FL, not 1000mm. A lot of the retailer ads have it wrong and says its 1000mm. I myself was intrigued when I first read about it, but later found out from looking at the PDF manual and those who bought it is that it is an F/7.9 of 900mm focal length.” So it’s not longer than London’s XT4.5, it’s essentially the same OTA.

This Meade is a pretty amazing deal. A lot of small intro reflectors have a short dovetail bar bolted to the side of the tube (like my old scope Shorty Fats), but this one has real tube rings and an EQ-2 mount. The three MA (Modified Achromat) eyepieces it comes with are nothing to write home about, but the focal lengths of 26mm, 9mm, and 6.3mm are at least useful and non-overlapping when doubled with the included Barlow. Terry shared a few views with me and I can confirm that it serves up a sharp, contrasty image, as you’d expect for a scope of this focal ratio. It would be a good deal at the list price of $170, but Amazon has it for $135 as of this writing, and according to Terry it can be found for even less if you look around.

I brought the Apex 127/SV50 combo – I’m sighting on the moon here, to align the finder with the scope – and the C80ED.

Here I am digiscoping the moon with the C80ED. I used the Apex 127 for tracking down some planetary nebulae and double stars, and the C80ED for photography and just messing around. It’s a crazy fun little scope. Unfortunately, none of my moon shots worked out this time.

The forecast called for clear skies most of the night, but clouds between 10:00 PM and 2:00 AM. We got set up before the sun set at 4:45, and pushed through until 10:40. Then it got too hazy to observe, so Terry and I sat and jawed about scopes, atlases, and observing projects until the sky cleared a bit at midnight. We got in about half an hour more before the sky clouded over completely about 12:40. We talked a bit more then turned in.

I got up at 4:00 AM to catch the morning planets – Jupiter, Mars, and Venus. I cannot get the iPhone to take a fast enough picture to capture any detail on Jupiter – it always comes out as a blank circle of light (with some glare from the iPhone, not the scope). But the moons show up nicely. I really need to get a better camera control app.

I was clouded out again at 5:15, and Terry and I sat up until 5:45 watching the approaching dawn. Then it started sprinkling! Weather Underground, the Clear Sky Chart, and my other weather app all missed that. We packed up quickly and drove out at 6:30. A hearty breakfast at the Coco’s in Indio put a cap on the expedition. Although the skies were less than perfect, we had a good time catching up, and we did see some nice things.

Back Again

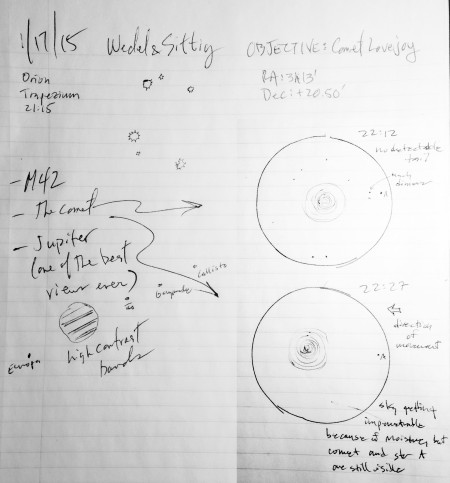

As luck would have it, I was back at the sea just eight nights later. London and I hadn’t been to the Salton Sea since last November, and he has all this week off from school, so we went last night. He took his XT4.5, and I took my C80ED. The waxing gibbous moon was only three days short of full, so the skyglow was pretty bad. But the seeing was excellent, easily 8 or 9 out of 10. I could split the four main stars of Orion’s Trapezium wide open at 25x, and fleetingly at 19x with the 32mm Plossl.

I could have held that split more easily with a better low-power eyepiece. I had not noticed it before last night, but my trusty Orion Sirius 32mm Plossl, my go-to widefield and finder eyepiece for many years, has some astigmatism. Not a lot – it was only noticeable immediately after switching from my 24mm ES 68. I tried both eyepieces with and without eyeglasses to confirm that the aberration was in the Plossl and not elsewhere in the optical train, my eyeballs included (I tried both). Another case of getting spoiled by premium eyepieces. It’s fine, though – since the 24mm ES 68 gives the same field of view, I only pull out the 32mm Plossl when I want to drop the magnification even lower, or when I’m doing outreach.

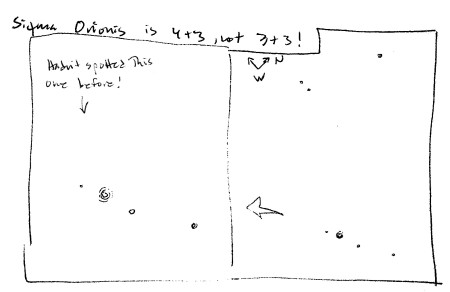

I spent a lot of time cruising the central part of Orion at 120x with the 5mm Meade MWA, which is now my preferred high-power eyepiece. Just three weeks ago I saw and sketched the multiple star Sigma Orionis for the first time. It’s funny – I’d been observing Orion regularly for eight years before that and I’d never seen it, but now I stop there every night I have a scope out. Even London’s little 60mm Meade refractor split the six main components wide open. But last night I saw a faint, seventh member that I’d previously missed.

I turned in relatively early, around midnight, figuring that I’d get up after the moon set and do a quick morning Messier hunt. And the sky was truly phenomenal after moonset. I was waking up about once an hour and having a quick look around, and it was a spectacularly clear, dark night. But the flesh was weak, and I overslept, only dragging myself out of my sleeping bag at 5:00. By that time the first glimmerings of dawn were lighting the eastern horizon, so I skipped the Messiers and went to Jupiter.

That planet above the scope is Venus, not Jupiter.

The view was jaw-dropping. The seeing was rock solid and I was able to Barlow the 5mm MWA up to 240x without the image breaking down. At that magnification I could detect at least three delicate brown belts north of the North Equatorial Belt, and the Galilean moons were little spheres, not just points of light. I tried taking some pictures but didn’t get any better results than I had the last time out, so I put the camera away and just stared. I must have spent 45 minutes just watching Jupiter drift across the field of view, mostly at 240x.

Last night I was definitely in aesthetic observing mode. I spent a little over two and a half hours at the eyepiece, entirely on four objects – the moon, Orion nebula and Trapezium, Sigma Orionis, and Jupiter. I had half-formed plans to look at other things, but I kept getting seduced into long sessions of fully immersed stargazing. And I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

So, neither night had perfect observing conditions. It was hazy the first night, and the moon was out during the convenient observing hours last night. But I had a great time both nights, saw some cool things, learned a little more about my gear, and enjoyed the good company of Terry and London. Couldn’t really ask for more.