Guest post: Whys and hows of astronomical sketching, by Doug Rennie

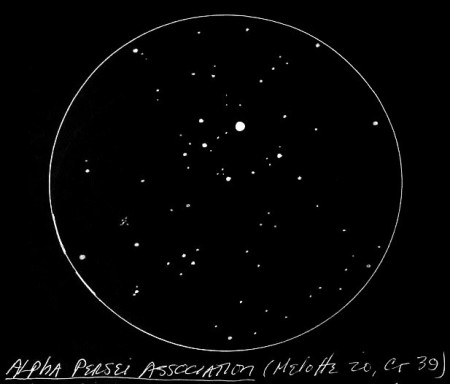

October 11, 2015Doug Rennie first opened my eyes to the value of sketching for the visual observer. I’m very happy to host his thoughts on the subject – and his sketch of the Alpha Persei association.

Sometime in the late-1990s, I wrote an essay on bibliophila, the love of books, for a literary journal. Thinking back, I recall two quotes I cited in that essay, one from an anonymous French book collector in 1851, the second from renowned literary critic Edmund Wilson – and both relate to the reasons why several years ago I made sketching a regular component of my observing routine.

“Owning a book puts it in your possession,” the Frenchman wrote. “But only reading a book makes it yours.”

For me, the same principle applies to stargazing. Locating and observing a celestial object, be it Messier, NGC, IC, asterism, whatever, produces a visual experience – and another box checked on your Objects Seen list. You now “own” it. Then, too often, you move onto the next one in the catalog, and just as quickly, the one after that. And so on. The impressions and mental images of the object you just minutes ago observed are already dim and vanishing fast in your memory’s rear view mirror.

But.

Not so if you regularly sketch what you observe. Because now you have to slow down, actually study what you see in the FOV, look at it through various eyepieces, seeing it both up close and large and bold – its own entity – and smaller and more subdued and part of a larger celestial context, the latter being what I personally prefer.

Then you put pencil to paper and sketch it.

One star dot at a time. Or perhaps you sketch it twice: Once at high magnification to capture all the detail and maximum star count, a second time pulled back to see both object and surrounding star field, the total celestial tapestry. By the time your sketch is done, you will have spent a half hour, sometimes more, in the company of this one single object. Moreover, you will have a permanent and personal hard copy of what you observed.

In the spirit of that anonymous Frenchman, you will have made the object yours.

The second quote, from Edmund Wilson, is this:

“No two persons read the same book.”

Think about it.

And this, too: Astronomical sketching is exactly the same. No two observers see the same exact object. If you want confirmation, hit a sketching site such as Deep Sky Archive and go to any object, say NGC 6633, and you will see a dozen sketches, often more, by different observers – and no two even look REMOTELY alike. I mean, you would think you were looking at sketches of 12 different objects. Sue French turned me onto this site over a year ago and I thought, Wow this will be great as I would now have a sense of what pattern(s) to look for in future first time searches. Nope.

If anything, more confusing (So, is This what it looks like? Or is it this one? Or . . . maybe . . . this? . . .)

Just as no two persons read the same book, it seems that no two observers see the same object. Even something as “clear cut” an image as, say, the Pleiades will have as many variations as there are observers/sketchers. So one more reason to make every object yours by laying out on paper the testimony of your visual senses for each object you observe on THAT night in THOSE skies with THAT instrument with THAT/THOSE eyepieces.

Now I’ve been observing for just over 3 years, and my background is all humanities, my hard science expertise zero. Or close to it. I am primarily an aesthetic observer who just enjoys drinking in all the beauty up there and, sad to say, pays scant attention to RA and Dec #s, Bortle Scale assessments of my sky that night, recording AFOV and TFOV, etc. I just go out and hunt down what I want to observe, and once I have what I’m after in the EP, I hang around it for a while. Most of the time, but not always, doing a sketch.

I began to sketch almost as soon as I started observing, and my early sketches are, well, “pitiful” would actually be kind. I was going to include one here to illustrate, but in the end could not bring myself to post one. Bad. These things are terrible. Third graders would laugh.

So here’s how I now go about it, and produce some decent-to-me results.

I have an artist’s sketchbook, spiral bound so it lies flat when opened, 8 x 10 inches, hard black cover. Cost under $10. My wife is an artist, so I initially used her drawing pencils, but quickly bought a set of my own at a local artist supply store: 2B, 4B, 6B, 8B, etc. Cheap. I store them in a plastic travel toothbrush case. I also use her recommended eraser, some artists’ gray plastic eraser, “Prismacolo” thing and it works superbly.

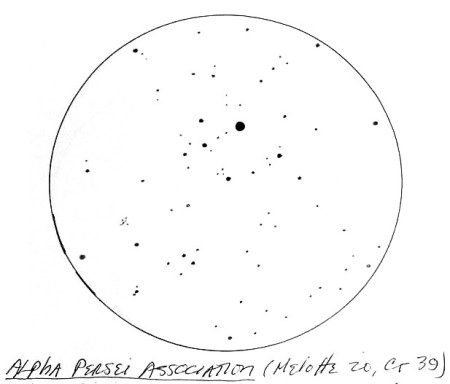

I have a scraggly small lined notebook that I use at the telescope and record in it a very rough first draft, focusing on accurate positions and spatial relationships among the stars, and taking care to use different size “dots” for individual stars commensurate with their brightness/dimness and size. I do a fair amount of erasing to get this draft, which is REALLY ragged, as accurate a reflection as possible of what I see.

I first do the outermost stars in all 4 directions just to make sure that I get the entire image I want in, then sketch in the anchor/biggest/brightest stars to get the main pattern. Once this is done, I work outward from there, one quarter section at a time. Seems to work.

The next day, I transfer the image into my sketchbook, now taking time to create perfectly round dots for every star and, often, using one of those plastic architect’s templates (3 bucks at Office Depot) for the larger stars, insuring that I get perfectly round dots for each. On the smaller stars, this is generally not a problem. See the attached sketch of the Alpha Persei Association. The two largest star sizes were done with the template.

A soft 2B pencil works best for most stars, but for the really tiny dim ones, of which there are generally quite a few, I go to a 2H or HB harder lead pencil which creates a lighter gray hue. When I have completed the entire sketch, I then take a very soft/dark 6B pencil, freshly sharpened and pointy, to go over the larger and darker stars to set them off, as they are through the eyepiece in “real time”, more dramatically from the background stars.

For open clusters, by far my favorite object to observe, I much prefer the look I get through one of my refractors (Explore Scientific AR102, Stellarvue SV80ED, Orion ST80) vs either of my Dobs, the largest of which is a StarBlast 6. With a Celestron 8-24mm zoom eyepiece in place for the first observation, I can go in and out, seeing the object large and up close with maximum stars, then widest field possible which puts the object at the center and gives it more context, and various degrees of both in between. Once I find the sweet spot, to me the ideal meld of object and context, I can go to one of my fixed focal length eyepieces, often an ES 16mm or Agena flat field 19mm. Some objects, such as the Double Cluster, look best in my ES 24mm/82 afov.

That’s it. Nothing more to see here. And, as you can deduce from the foregoing, sketching is NOT all that difficult. I mean, c’mon, it’s not particle physics. So if you’ve not already included sketching as a regular part of your observing, why not give it a test drive next time out?

REALLY LIKED EVERYTHING in this.Thanks for the “PUSH ” to record what you see out there. regards, rich.

Thanks for the nice words, rich. The next step is up to you! I’d love to see what you come up with, so please send some of your efforts to Matt for posting.

Doug

Thanks for sharing your methodology Doug. Sometimes I’ll use a lined notebook, other times a blank notepad – whichever is available at the local convenience or drug store when I’ve run out of pages from my previous sketch book or pad.

Hi Terry. Yes, you and I have previously shared thoughts on sketching. Our approaches are quite different, but like every other aspect of observing, or life period, there is no one-size-fits-all method. I probably expend a lot more time than I need to on sketching, but it’s something I enjoy doing.

Now, about you and that 82-degree eyepiece . . .

Doug

[…] to split some doubles (Eta Cass was nice) and look at the Double Cluster. Didn’t attempt a sketch, I was just rolling for aesthetic appreciation, but I did use a lot of magnification and spent more […]

[…] commenter and sometime contributor Doug Rennie recently took possession of a Celestron NexStar 6SE Schmidt-Cassegrain with GoTo. He […]